We Bleed the Same: Reflections on an exhibition combating racism through the arts

17 June 2022

Are you a Star Wars fan?

Ewan McGregor, lead actor and Executive Producer of the new Obi-Wan Kenobi TV miniseries posted a video message to millions of Star Wars fans on 1 June 2022 in support of his co-star, Moses Ingram, who was being racially vilified online. McGregor started by thanking the fans of the show but said that:

…some of the fanbase […] have started to attack Moses Ingram online and send her the most horrendous, racist DMs and I heard some of them this morning, and they just broke my heart. Moses is a brilliant actor, she’s a brilliant woman and she’s absolutely amazing in this series. […] I just want to say as the leading actor on the series, as the Executive Producer on the series, that we stand with Moses, we love Moses and if you’re sending her bullying messages, you’re no Star Wars fan in my mind. There’s no place for racism in this world.

The Star Wars franchise also posted a message of support to their six million Twitter followers. This is just a very recent example of a pernicious issue and while it’s great to see huge franchises and high profile actors calling out racism, but this alone is not a solution. Tackling racism and bigotry is a complex issue that can’t be fixed by a social media post or celebrities, even if they can engage a large audience. There are deeper issues, and no quick fixes.

Racism and bigotry have caused major problems in our society, stemming in Australia from a foundation of a nation built on systemic racist laws and powers targeting ethnic minority groups and First Nations people—the traditional landowners.

My parents, who migrated from Lebanon, were subjected to racism on a daily basis at our corner store. We were subjected to racial abuse, which my father often confronted, and one morning we woke up to find ‘Wog Shop’ sprayed in red on our store’s front window.

Despite all this my parents are proud to call Australia home. We had the best of both worlds, growing up as Aussies, enjoying daily trips to the beach, barbecues, Vegemite on toast, and the best of our Lebanese culture – home-cooked Lebanese food and speaking Arabic. It is my personal experiences with racism and drive to protect my children and family that drove me to create and produce an exhibition and documentary—both called ‘We Bleed the Same’.

I had the idea over ten years ago but a community-based campaign I was involved in, called ‘Racism Not Welcome’, prompted me into action. My We Bleed The Same exhibition is a space for an audience to view and experience the deeply personal stories of people who have been subjected to many forms of racism. The exhibition features 35 incredible people from varied backgrounds, races, and religions bravely sharing their stories on film in the documentary, and through portraits taken by my colleague, leading photographer Tim Bauer.

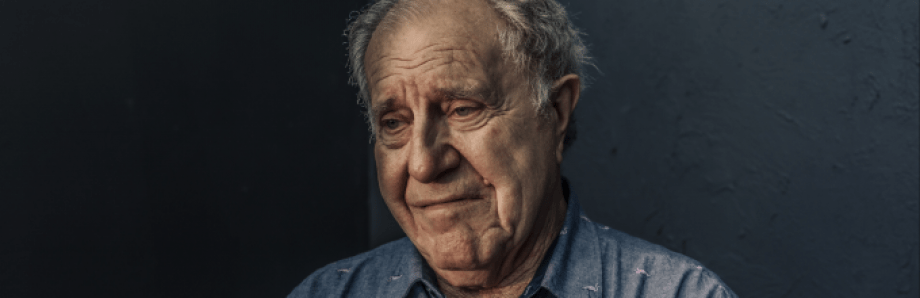

One story, told by Holocaust and Hungarian ghetto survivor, Ernie Friedlander, brought us to tears. For our documentary he relived his heartbreaking yet inspiring story of the horrors of the Second World War. Yet years later, after settling in Australia, Ernie encountered racism of another kind. He recalled a stranger in a business suit yelling at him over a carparking space in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, saying ‘More people like you should be put in the oven.’

Another participant is First Nations Wailwan, Wongaibon Elder and Stolen Generation survivor, James Michael ‘Widdy’ Welsh, affectionately known as Uncle Widdy. When he, too, was seven, he was ripped apart from his family:

I was told I would be number 36. If I used my name I was beaten, abused, treated less than an animal in the evil Kinchella Boys Home we were forced to stay in. People say we were stolen. I don’t like that word. I’m not an object, I’m a human being who was kidnapped from my family, thanks to a racist government policy. I lost my culture, identity and family and spent my whole life trying to drink my pain away, suffering, in and out of prison for 45 years. I’m still learning about my heritage and trying to heal in my seventies.

These stories, and the thirty-three others like it, demonstrate the depth of hurt and trauma caused by racism—be it institutional or everyday.

Many visitors to the show have been shocked and devastated by these stories and by the experiences people have been forced to endure. Some have left the exhibition in tears hearing Uncle Widdy’s story and feeling ashamed that this country implemented such cruel policies that inflicted unimaginable pain, suffering and intergenerational trauma. Yet despite the pain, Uncle Widdy is forgiving: ‘I don’t want people to give us sympathy, we want understanding, knowledge about what we’re doing and understanding to be treated like everybody else.’

This longer form storytelling gives the audience a deeper insight into the person’s lived experiences. It’s a rare opportunity to step into their lives and gain a sense of their trauma, but also their incredible strength and power in surviving and fighting for positive change for the next generation. This can be a powerfully moving experience.

One visitor fell into my arms crying after viewing the show. She told me:

I was shaken and shocked with my emotions. I had to question myself after seeing your powerful show… I thought I was an inclusive person. I’m not a racist but I found that I was questioning myself when I felt prejudice against a certain race. I had to leave and think about how I felt and explore my emotions and beliefs. I’ve returned to see the show with a fresh perspective. It’s changed my way of thinking of others.

This is the power of the arts to challenge racist views. It is not simply enough to challenge racism, or call it out when we see it, although this is important. The stories told by Ernie and Uncle Widdy, and many others, help an audience see through the eyes of those we might not understand and give them new perspectives. Their stories, told emphatically and empathetically, help us see the world from their perspective.

But racism remains a major problem in Australia. The Amnesty International inaugural International Human Rights Barometer, published in 2021, stated that while 84% of Australians believe in freedom of religion and culture, less than half (47%) believed there was a problem with racism and more than a quarter thought there was no problem with racism at all. Almost two thirds (63%) said they believed some ethnic groups and cultures did not want to fit into the ‘Australian’ way of life. The Australian Human Rights Commission investigated prejudice against Muslims in Australia. This report found a shocking 80% of Muslim Australians had faced unfavourable treatment based on their ethnicity, race or religion. This racism takes the form of hate, violence or negative comments in public. Yet Maryam El-Kiki, 25-year-old school teacher and another participant in the exhibition, reminds us that she has more in common with other Australians than they might think: ‘I’m a proud Australian Muslim woman. I do all the things that you do. I go hiking, horse riding and go the beach. Please don’t let a piece of material I choose to wear get between you and me.’

If you would like to be part of the We Bleed the Same exhibition, combating racism, and celebrating diversity, please contact Liz Deep-Jones: webleedthesame23@gmail.com.

The We Bleed the Same exhibition is free and currently showing at the Australian National University, Level 1 and Level 2 of the RSSS Building, 146 Ellery Cres. Acton, ACT until 21 February 2023. To find out more, go to: We Bleed the Same.